Hough, Samuel J., III, died March 4, 2019 of complications from diabetes. Husband of Penelope (Otis) Hough, he was born in Philadelphia, PA, son of the late Samuel J. and Margaret (Hoffman) Hough. He was the father of Matt Hough of Warwick and the late Claire Hough; brother of Brian Hough, Sherna Deamer, and Bonnie Rose Hough, all of California; and grandfather of Kevin Hough of Springfield, Missouri.

The memorial gathering will be held Saturday, April 6th from 10:00 AM - 2:00 PM at the Palestine Shriners, One Rhodes Place, Cranston, RI 02905

quote:

How to become a bibliomaniac

By Joe Kernan

November 30, 2011

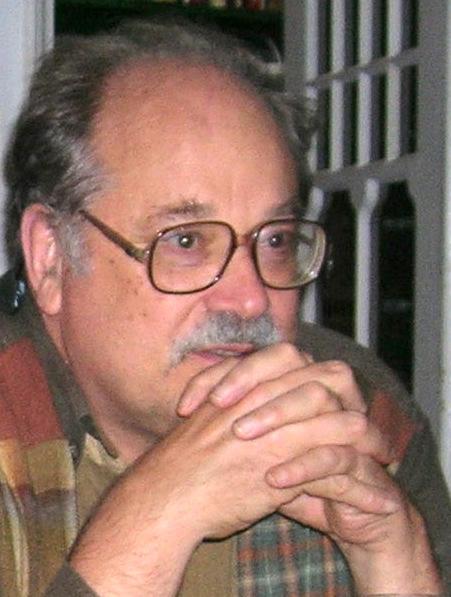

He looks like a typical suburban retiree, with his home in Edgewood showing the desultory affect of a homeowner who didn’t do landscaping for a living. But it is a respectable unkemptness and certainly not the sort of property that has his neighbors complaining to minimal housing about.

In short, Sam Hough’s Edgewood home shows all the signs of a home that focuses more on what happens on the other side of the threshold.

Sam Hough is a bookseller and his living room is a wonderland of books and relic-like gewgaws that people of that profession are inclined to accrue. True, there are owls about the place, in prints, as figurines and by other representation but that is not why he calls his business The Owl at the Bridge.

“Obviously, we like owls but the name came from being near the Pawtuxet Bridge and the image of an owl at the bridge appealed to me,” said Hough (pronounced “huff”).

Although he once did have a small space on Broad Street when he started selling books in the 1980s, the brave new world of inflated real estate costs and diminished foot traffic made maintaining the space impractical.

“I do keep some of my stock here in the house but I also have 2,500 square feet of storage on Wellington Avenue,” he said. “Our book shop was always much too small for the space we needed.”

Like most booksellers in the digital age, Hough has adapted to the world of online bookselling. In fact, very few used bookstores could sustain themselves by walk-in sales alone. Catalogs and mail order have been a major part of the rare book business for centuries but Goodspeed’s, The Brattle Book Shop and other small stores in Boston made good money catering to leisurely walk-ins or the lunching masses that haunted the 25

and 50 cent tables everyday. Now, if Sam Hough wants to get his hands on a good book, he has to go to a public or private library. He won’t find the bookstores of his youth in Philadelphia, or his salad days of acquiring books for college libraries. There are no easy fixes for a bibliomaniac these days. Everyone is waiting for the mail, or, as some would have it, the “snail mail.” We must wait, anxiously and tensely, for our junk to come from the Post Office or UPS.

These are bad times for book addicts.

But that was how I met Sam Hough. I was nostalgic for Goodspeed’s, as I frequently am, and ordered two copies of the 75th Anniversary catalog online. I was pleasantly surprised when they arrived in my mailbox with Cranston as a return address. Needless to say, I was pleased to know there was a local “dealer” I could turn to when I had the urge to own a rare book: my connection.

I have a disorder that has not been publicly discussed much. I am neither proud nor ashamed of it. If I have been reluctant to speak of it publicly before, it was because that may draw more people and competition for what we desperately crave; old, rare and special interest books. For we are bibliomaniacs:

“Bibliomania or Book-Madness; from the Greek biblion=book +

mania=madness. Behavioral disorder…Common symptoms include the uncontrollable urge to acquire and hoard books; indiscriminate bookstore hopping…which alone or in combination may result in prolonged disruption of daily life. The more severe forms of bibliomania may involve recurring incidents of bibliokleptomania (book theft)…No cure is known to exist…” www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Bibliomania

The Gutenberg Project’s definition may be a little too broad. We usually are more selective and prone to specialize: First editions, Americana, early printing or incunabula; military history, exploration, any subjects that have engendered a number of cool books. I’m more of a generalist; having spent many idle hours hiding out from truant officers in the Boston Public Library as a youth and having idled even more as an apprentice bookseller at Goodspeed’s. Sam Hough’s specialty is Italian books and printers, with formidable digressions into other areas.

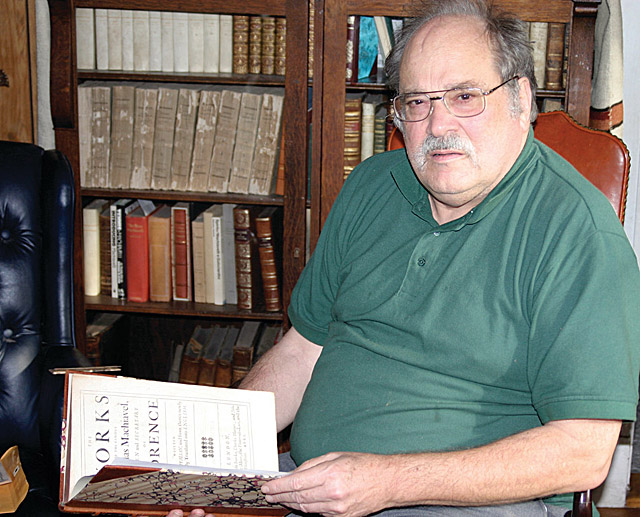

“One of the very first books I bought was a 1847 edition of ‘The Book of the Courtier’,” said Hough, as he explains his early descent into bibliomania. “What I liked was the sheer physicality of old books, of old paper.”

Hough’s interest in books lead him to more esoteric areas of expertise that have served him well. He is an acknowledged expert on Gorham Silver, as well as Italian printers and books. He was a consultant to the Johnson and Wales Culinary Arts Museum, to help them flesh out their collection. That was after he did acquisitions for the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University and was an archivist at The University of Pennsylvania after studying library science at Columbia. He has published definitive reprints of Gorham catalogs and regularly speaks to groups about books and libraries and Gorham. He has done what he had to do to stay close to sources that feed his bibliomania. But Hough has done it in a benign way. Others have not been as reasonable.

For instance, there was a Methodist pastor of the Mathewson Street Methodist Church in Providence who brought shame to booklovers in 1881 when he was exposed as a book thief and a liar. He pilfered from the Providence Athenaeum. He would steal the books, rebind them and claim he “found” them at incredibly bargain prices locally and in Boston. He took the rare “Key into the Language of America” by Roger Williams, had it rebound and announced that he found it in a trashy heap in a bookstore in Boston and got if for $1. Eventually, his knack for finding bargain books aroused suspicion. A search of his collection returned at least 10 books to the Athenaeum with their library markings clumsily removed or disguised. Unfortunately, I only found one story about Rev. W.F. Whicher’s crimes and absolutely nothing about where it brought him criminally and socially.

There were more unhappy tales of bibliomania.

In his 1944 article, “Book Row,” in the Saturday Evening Post, Don Samson gives a brief history of a bibliomaniac that haunted the area.

“A shoe clerk from Brooklyn wandered into one of the secondhand bookshops on Book Row. He had never bought a book in his life, but picking up a musty volume, he liked the feel of it and bought it. The more he handled it, the more he liked it. He began buying books…Finally, his wife couldn’t take a bath because the tub was full of books…and threatened to go home to mother unless he got rid of them. He did. But within two weeks he was buying books again…She went home to mother.”

In 1994, Harper’s Magazine profiled a modern Rev. Whicher taken to the extreme.

In “The Book Thief: A True Tale of Bibliomania,” Philip Weiss described Stephen Blumberg, who was convicted of stealing over 20,000 books, manuscripts and papers from public and college libraries:

“The West Coast thefts had the effect of bringing into the Blumberg case its most approachable figure, a rangy, good-looking Washington State University campus police detective named J. Stephen Huntsberry. In February 1988, librarians at WSU discovered that precious Mexican manuscripts were missing. Sergeant Huntsberry was sent over to investigate. When a librarian used the term ‘incunabula,’ Huntsberry

frowned. The librarian explained that it referred to the infancy of printing, and to demonstrate handed him a book printed in 1493. It occurred to Huntsberry, as he turned its pages and smelled the mold of ages, that Columbus could have read that book.

“‘That's when I got hooked,’ he [Huntsberry] told me.”

As for Sam Hough, you can discuss such bibliomaniacal oddities when you go to him to get your fix of rare books, right here in the West Bay.

“Books are easy,” Hough will reassure you. “It’s people who can be difficult.”

SMP Silver Salon Forums

SMP Silver Salon Forums

General Silver Forum

General Silver Forum

Samuel J. Hough - Authority on Gorham Silver - RIP

Samuel J. Hough - Authority on Gorham Silver - RIP