quote:

THE LAND DIVIDED,

THE WORLD UNITED:

A Historical Account Of

The Panama Canal on Spoons

by Connie Halket

Photos by Jim FrinkOn the morning of August 15, 1914, the S. S. Ancon was poised and ready to make history, for to her had fallen the honor of being the first ship to pass from the Atlantic to the Pacific through the new interoceanic canal at Panama. Elsewhere in the world most eyes were upon the recently-declared war in Europe, the war which would eventually reach such proportions as to be called "The Great War." Austria had just declared war on Serbia, hurling the world unexpectedly into the throes of the escalating war only a few days earlier, and few were interested in the momentous event about to take place in the quiet jungles of Central America. Yet the occasion was to mark the completion of one of man's greatest engineering feats of all time, a triumph of the human spirit over great odds.

Approaching the gates of Gatun Lock promptly at 8:00 a.m., the S. S. Ancon floated quietly into Gatun Lake. No ribbon was cut nor special ceremony undertaken to mark the severing of two continents, but a band played while a few local dignitaries watched from the decks of the ship and thousands of workers lined the shores as the ship passed by construction camps. From Gatun, the largest artificial body of fresh water in the world, the ship progressed toward the Culebra Cut past Cucaracha Hill, an area known for its horrible landslides, finally arriving at the locks at Pedro Miguel at 12:56 p.m. The Ancon was locked down into Miraflores Lake, a smaller man-made lake, at 3:20 p.m., ending her journey at the docks in Balboa at 5:10 p.m. The chief engineer of the canal project, George Washington Goethals, rather than sailing with the Ancon, chose to parallel her trip on the canal railroad. Surely, it was the greatest day of his life, yet strangely he preferred to view it as a spectator rather than as a participant.

James Bryce, in his book, South America: Observations and Impressions, comments, "There is something in the magnitude and the method of this enterprise which a poet might take as his theme. Never before on this planet have so much labour, so much scientific knowledge, and so much executive skill been concentrated on a work designed to bring nations nearer to one another and serve the interests of mankind." Yet the world was scarcely noticing any of it now. "The land divided, the world united" was the motto incised upon the great seal of the Canal Zone, but the world in August, 1914, was far from united.

Such a canal had existed in the dreams of men long before the United States was born. Groups of early explorers sought passageways to circumvent what they believed to be huge islands, but which were in fact the coastline of two huge hemispheres. In September, 1513, Vasco Nunez de Balboa crossed the narrow Isthmus of Darien and became the first white man to gaze upon the ocean which he named the Great South Sea. Six years later, Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese sailor, encountered a passage at the tip of South American which still bears his name, but the route was too far south and much too tortuous and turbulent to be practical for commerce or travel. It was Magellan who named the calm, serene waters on the western side of the strait "Pacific," the Spanish word meaning "calm," after surviving the treacherous voyage from the Atlantic Ocean.

Earliest plans for a canal separating the continents date to the Sixteenth Century when Charles V of Spain instructed Hernando Cortez to search for a passage during his conquest of Mexico. None was located, but Alvaro Saavedra, a lieutenant of Cortez', drew up plans for digging a canal at the next to narrowest point on the isthmus at Venta de Cruces. But neither his plan nor a later one, which incorporated a hundred-mile inland lake in its route through Nicaragua, ever left the drawing-board stage.

Other sites, such as the flat land at Tehuantepec, Mexico, were also considered, but at the end of the century the glory of Spain's armies had faded and feeling was strong that such a canal, if it were built, might be of more benefit to Spain's enemies, serving to break Spanish hold on the American colonies she needed so desperately to keep. Oddly enough, the next organized effort to cut away at the isthmus came from William Paterson, a Scottish farmer's son, who had earlier conceived of and organized the Bank of England. He considered the isthmus to be "the key to the Indies and door of the world." Although he was never to set foot on Panamanian ground, he proposed the building of an interoceanic highway whose controllers he believed would be the pivotal powers of the world, monopolizing world trade and hence world wealth. Unfortunately, local politics caused the British government to reject funding such a project, so Paterson formed the Darien Company through private subscriptions.

Though it suffered great pains - an official absconded with much of its assets and England refused to sell it ships - the Darien Company eventually sent an expedition to Panama equipped with such ludicrous impractical's for trade as 4,000 wigs and 6,000 pairs of stockings. Furthermore, the Dutch and English settlers there had been instructed not to trade with them. Unfortunately, they were able to buy brandy and beer, making drunkenness the number one problem in short order. And while three ministers had sailed on the voyage in order to deal with men's souls, not a single physician came to attend to the diseases of the body. Of the 1200 who arrived, 744 perished and only a handful returned to Scotland in 1699. A second party of 1300 had already embarked without knowing similar fates awaited them in the unknown land. In the end, the affair cost the optimistic Scots £300,000 and an appalling number of lives, only to be recognized as a national calamity. Today, Caledonia Bay and Punta Escoces (Point of the Scots) remain on Panamanian soil as silent reminders of the Darien Company's valiant efforts.

By the early Nineteenth Century, the colonies were rapidly breaking away from the old world rule of past centuries, but they were encountering strong difficulties in establishing strong governments of their own. The newly-emergent American states were too strong to return to Spanish governance, though too weak to survive alone. The European Holy Alliance (Russia. Prussia. AustriaHungary), which claimed to be inspired by Christian charity, justice, and peace, now had its eyes locked upon the New World. President James Monroe. surveying the situation carefully, declared to the U.S. Congress "that the American continents by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintained, are henceforth not to be considered as subject for future colonization by any European powers .... " He went on to state that the United States would not interfere with existing colonies in the New World, but that they also would not allow foreign powers to tamper with countries in this hemisphere which had already declared independence.

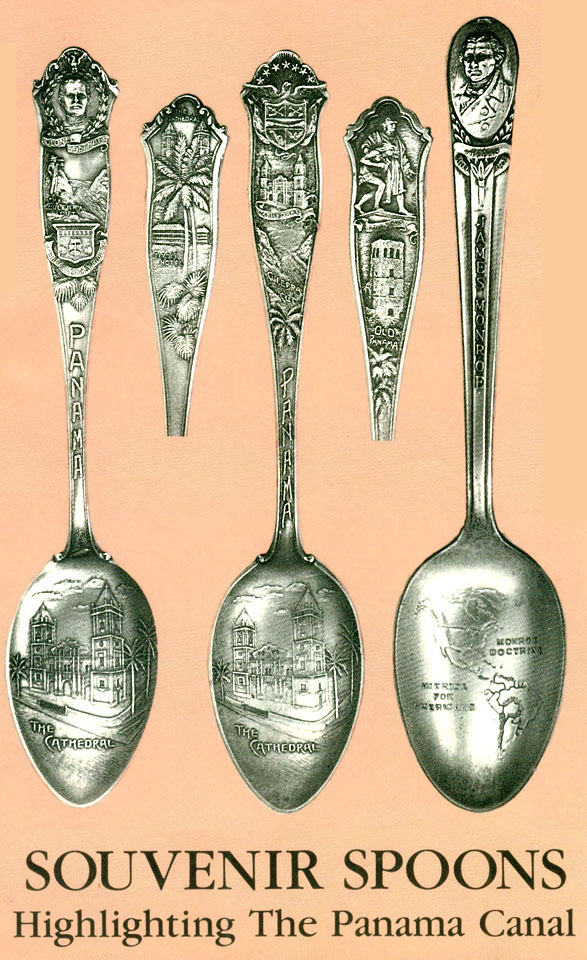

In Panama. where the annual average temperature is eighty degrees and the climate is conducive to the growth of many of the 1500 known varieties of palm trees, these thick-stemmed, un· branched evergreens, topped individually with a cluster of large, simple, palmate or pinnately compound leaves, have enormous economic importance. In the tropics, nearly every part of the palm tree is used for food, construction of homes and household goods, or industrial raw materials. The official seal and motto of the Canal Zone is superimposed against feathery palms, indigenous to the five mile strip of land through which the Panama Canal is cut, on the spoon in Figure 1 , manufactured by the Charles M. Robbins Company after the completion of the canal. The Watson Company, of Attleboro, Massachusetts, produced the souvenir in Figure 2 in conjunction with the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915. The entire length of the spoon is devoted to mapping the canal from lock to lock. The spoon is also unique in that it must be viewed from the north looking southward, indicative of how most Americans conceptualized the whole Panama adventure.

A pair of spoons in Figures 8 and 4, also produced by Charles M. Robbins, feature the Cathedral at Cathedral Plaza in Panama City, where the principal religion of the Spanish. speaking population remains Roman Catholicism. George Washington Goethals, chief engineer of fittingly encircled by laurel wreaths honoring his great contribution to humanity, while below a surveyor keeps vigil over the Culebra Cut. On the reverse, the spoon depicts the Tivoli Hotel, a large, three-story frame structure at Ancon, begun in 1905 and whose construction was hurried along by then chief engineer, John Stevens, in anticipation of the arrival of President and Mrs. Theodore Roosevelt on November 6, 1906. One wing was finished and furnished in six weeks because Mr. Roosevelt had requested to lodge on shore rather than aboard ship. The reverse of the second spoon features ruins at Old Panama and a bronze statue of Columbus with an Indian maiden at his side. A gift from the Empress Eugenie, the statue originally stood in a railroad yard in Aspinwall, also known as Colon, the canal project, tops the first spoon, on Manzanillo Island at the entrance to Limon Bay. John Stevens had christened the town in honor of William Henry Aspinwall, a founder and financier of the canal railroad, but others preferred to call it Colon after Columbus, a dispute which has continued over the years.

Figure 5, a spoon from Wm. A. Roger's presidential series, characterizes James Monroe whose policies so influenced the Western Hemisphere. The silverplated spoon echoes the popular slogan, "America for Americans," as it commemorates Monroe's important contribution, the Monroe Doctrine.

The Nineteenth Century was filled with growing pains of the largest dimensions. Land boundaries changed, then changed again, and most significantly, private industry mushroomed in both hemispheres. Now investigating the feasibility of an interoceanic canal were names like DeWitt Clinton, Thomas Jefferson, and Ben Franklin. In 1848, the California Gold Rush served to stress emphatically once and for all the need for quicker routes from sea to sea, for the railroad systems of the United States had not yet pushed west of St. Louis. Many gold prospectors journeyed to Vera Cruz, Mexico, by ship, proceeding west from there by land. The United States government subsidized two steamships, one from New York to Chagres, a village at the mouth of the Panamanian river of the same name, and another from San Francisco to the city of Panama. New York financiers, William Henry Aspinwall and Henry Chauncey, who were directors of the company responsible for the Atlantic connections, together with lawyer and distinguished archaeologist, John Lloyd Stephens, formed the Panama Railroad Company to construct a rail line across the isthmus to connect the two steamship lines.

Labor troubles were imminent. The engineers had hoped to enlist local labor, but the natives had other interests. About a thousand Chinese were imported, and while the employers attempted to keep them happy and productive by serving ethnic foods and making opium available - for the stereotype of the era purported that all Chinese used the drug - the work proved too strenuous for them and the climate too hot. They committed suicide in droves and many more were claimed by cholera, dysentery, malaria, yellow fever, and smallpox in a country where still not a single physician or hospital had been provided.

The company tried Irishmen, Frenchmen, and, finally, Negroes from Jamaica, the latter proving hardiest, but "incurably lazy." In truth, they understood the limitations of the tropics and were unmotivated to produce at higher levels. Rumor had it that every tie on the Panama Railroad cost a laborer's life. In fact, there were 74,000 ties laid for the single track, narrow gauge railroad, and over 20,000 lives were expended, a truly incredible price. In the pouring rain, midnight, January 7, 1855, the final section was laid, uniting the two oceans by rail.

It was the shortest major railroad in history, 47,57 miles, and it charged the highest rates anywhere, about twenty five dollars for one-way passage. Indeed, it has been the most expensive railroad ever built, costing eight million dollars, or about $168,000 per mile. StilL because of the impatience of gold seekers coupled with the exhorbitant rates charged, the railroad took in over two million dollars before it was even finished. When it was sold to French interests in 1880, a controlling share in the line brought more than eighteen million dollars. The railroad succeeded in every other way as well, paying larger dividends than any other railroad had ever dreamed possible and transporting an astounding amount of gold bullion from California to the East (over $750 million) until the driving of the Golden Spike in Utah united the United States' railroads in 1869.

The Mid-nineteenth Century saw names like Vanderbilt, Walker, and Morgan entering into the task of building a canaL but Europe was embroiled again in war (Crimean War, 1854), and the United States was moving towards its own disaster, the Civil War. The Holy Alliance made one last attempt to plant royalty in the Western Hemisphere by placing Maximilian and Carlotta in Mexico. Times were indeed changing and the Industrial Revolution was underway. The need for a canal passage was never more evident. What remained was the choice of a location (Nicaragua or Panama) and the actual ground-breaking.

Frenchman, Ferdinand de Lesseps, believed a sea-level canal best suited to the Isthmus of Panama. He estimated the time at eight years and the cost at $168 million. His organization, La Campagnie Universelle du Canale Interoceanique de Panama, became more than just a private enterprise, taking on proportions of a patriotic crusade under his charismatic salesmanship. The grisly truth, however, was that during the eight-year French effort, 20,000 men died, most of them victims of tropical diseases. The project fell into disfavor and the worst thing you could call a man was "Pamaniste." Clearly, all the foreign efforts could be summed up in one dismal word: failure.

Americans were finally beginning to catch the vision that a canal would be their duty. On June 28, 1902, Congress passed the Spooner Act authorizing the President to buy the assets of the New Panama Canal Company, the successor of the French company, for forty million dollars, to arrange the necessary treaties, and finally to build a canal "for convenient passage for vessels of the largest tonnage."

The youngest and certainly one of the most effervescent men ever to sit in the White House, Theodore Roosevelt, was a proponent of direct action. It was not surprising that he would be the one to get the dirt flying. John Frank "Big Smoke" Stephens was also heralded as a man who got things done, and as the new chief engineer, he quickly assessed the situation in Panama. "There are three diseases here," he said, "malaria, yellow fever, and cold feet, and the worst of these is cold feet." One by one he saw to the elimination of the threat of all three, closely supervising everything himself. He viewed the project then as a massive railroad job to prepare the way for the building of not a sea level canal, but a lock canal. However, Washington saw it differently. Stephens replied that if Washington planned to build the canal in sections and ship it down to him, he would leave the project. Ten thousand employees signed a petition begging Stephens to stay, but neither Roosevelt nor Stephens could bend enough to tolerate each other and Stephens, despite his magnificent beginnings, left the project.

Roosevelt promptly determined to appoint a chief engineer who could not quit. His secretary of state, William Howard Taft, appointed George Washington Goethals, a colonel in the corps of engineers, to succeed the popular Stephens. Goethals's strong point was systematization and he quickly implemented his master plan.

That plan included a dam across the Chagres River at Gatun near Limon Bay in the northern (Atlantic) end of the can al- to-be. The damned-up water would create a lake backing up through the mountains called the Culebra Cut, and on the Pacific end, another body of water, Miraflores Lake, would form behind three sets of locks which would allow vessels to come and go simultaneously.

From its opening in August 1914, the canal was a commercial success. Total passage time averaged eight or nine hours, with tolls levied according to size and weight of the vessel and the amount of the cargo carried. An average toll figure was about $5,000.

Presently, the canal handles about 12,000 ships yearly, operating twenty four hours a day and employing 14,000 persons, 4,000 of which are Panamanians. While the canal is not sufficient for its load, to widen it would be outrageously expensive. By 1970, thirty sites had already been investigated for a new canal project, the most popular being at Tehuantepec, Mexico, and others in Panama, Colombia, .and Nicaragua. A new excavation most probably would be undertaken with nuclear devices. Since one of the major weaknesses in the present canal is its lock system which could be knocked out for months if bombed, a new canal most likely would be at sea level Such a canal would also be less costly to build and maintain and could be deeper and wider. It is feasible, and perhaps even probable, that a new interoceanic canal will be constructed "with a bang," as historian Donald Chidsey suggests. Since politics have been an on-going nemesis for the present canal from the times even before its inception, most certainly an effort to open a new passageway ought to be truly pan-American.

Spoons in Figures 6 through 9 feature views of the infamous Culebra Cut, blasted from the mountainous interior of the isthmus. Construction of the canal consumed 61,000,000 pounds of dynamite, a greater amount of explosive energy than had been expended in all nations' wars until that time. Half of the canal labor force was in fact employed in some phase or other of dynamiting. In these scenes of the Cut, the railroad, equipment, and work camps are also chronicled on silver. The handle of the spoon in Figure 7 illustrates the machine responsible for building the canal ditch. Shovels of this dimension employed by Col. Goethals set records never anticipated as they seemed to take on personalities and feminine gender while tales of their prodigious feats earned them a mythical quality. The peak was recorded in March 1909, when sixty-eight shovels, the largest number in use at one time in the Cut, removed more than two million cubic yards of earth in one month, ten times the volume achieved by French predecessors in their best month. The record for a single shovel was registered by a ninety-five-ton Bucyrus, No. 123, working twenty-six days in March 1910, excavating 70,000 cubic yards. The total volume removed from the Cut was ninety six million cubic yards, an average of a million per machine. Theretofore no machines had ever been subjected to such strenuous testing, a fact which made their records a tribute to their designers and operators.

Figure 6 shows an entirely gold-washed spoon with a champleve enameled crest in three shades of blue as well as green, white, and red. The process is achieved through cutting troughs in the metal, into which the frit, or enamel, is melted. Finishing includes grinding the enamel flush with the metal and final polishing.

Figure 9 pays tribute to the men who "made the dirt fly." The statuesque figure, sleeves rolled high and pick in hand, recalls to the mind the cost of the canal in terms of human suffering and death. The worst single accidental disaster of the project occurred at Bas Obispo on December 12, 1908, when twenty-two tons of dynamite exploded prematurely, killing twenty-three and injuring forty.

Stamped with "I.C.C. Hotel," the silver- plated wild rose pattern spoon in Figure 10 from the Adams Manufacturing Company probably reminded workers of home in the States. "Original Spoon has been used by the Panama Canal Builders, I.C.C. Hotel, Isthmanian Canal Commission Hotel, Panama" raised in its bowl, it reminds us now of the camaraderie among the workers of the colony so far from home. The I.C.C. made every effort to establish a model community within the Canal Zone both as comfort to its workers and as an "edifying example for Panama and the rest of Central America." The entire social order of the community existed on the work ethic and members were rewarded according to the importance and amount of their work. The I.C.C. Hotel was another link in a long chain of residences, gyms, clubs, churches, and stores owned and operated by the commission. There a worker could purchase a meal worth seventy-five cents for just thirty cents while he socialized with friends.

Figures 11 and 12 are representative of the many commemorative spoons produced for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition which opened February 20, 1915, in San Francisco. Celebrating the opening of the canal as well as Balboa's discovery of the Pacific Ocean, emphasis of the fair was on artistic and cultural values rather than invention and industry promoted in previous fairs. In this vein, a plated spoon produced as a promotional by the California Perfume Company (now Avon Products, Inc.) features on its reverse the beautiful Court of the Four Seasons and on its obverse, the Palace of Liberal Arts and the Tower of Jewels, the latter being the official symbol of the fair and known for its outstanding lighting effects. The inscription on the spade in the bowl of Figure 12 reads: "Used by William Howard Taft, President of the United States, October 14, 1911, in turning the first spadeful of earth for the PanamaPacific International Exposition to be held in San Francisco 1915." Thirty-six nations participated in the fair which was visited by thirteen million people in its brief existence. The doors closed on December 4, 1915, after a nine and one half month run.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chidsey, Donald Barr. The Panama

Canal: An Informal History of Its

Concept, Building, and Present

Status (New York: Crown Publishers, "

Inc., 1970), 216 pages.Hardt, Anton. A Third Harvest of Souvenir

Spoons (New York: privately

printed, 1969), pp. 104-5.

Hardt, Anton, New Discoveries in Historical

Spoons (New York: Greenwich

Press, 1977), p. 143.

McCullough, David. The Path Between

the Seas (New York: Simon and

Schuster, 1977), 622 pages.

Rainwater, Dorthy T., and Felger,

Donna H. American Spoons, Souvenir

and Hiatorical (Hanover, PA;

Everybody's Press, I968), pp. 249-54.

Rainwater, Dorothy T., and Felger,

Donna H. A Collector's Guide to

Spoons A round the World (Hanover,

PA: Everybody's Press, 1976), pp.

335-7.

Schott, Joseph L. Rails Across Panama

(Indianapolis, IN: The Bobbs-Merrill

Company, Inc.), 207 pages.