quote:

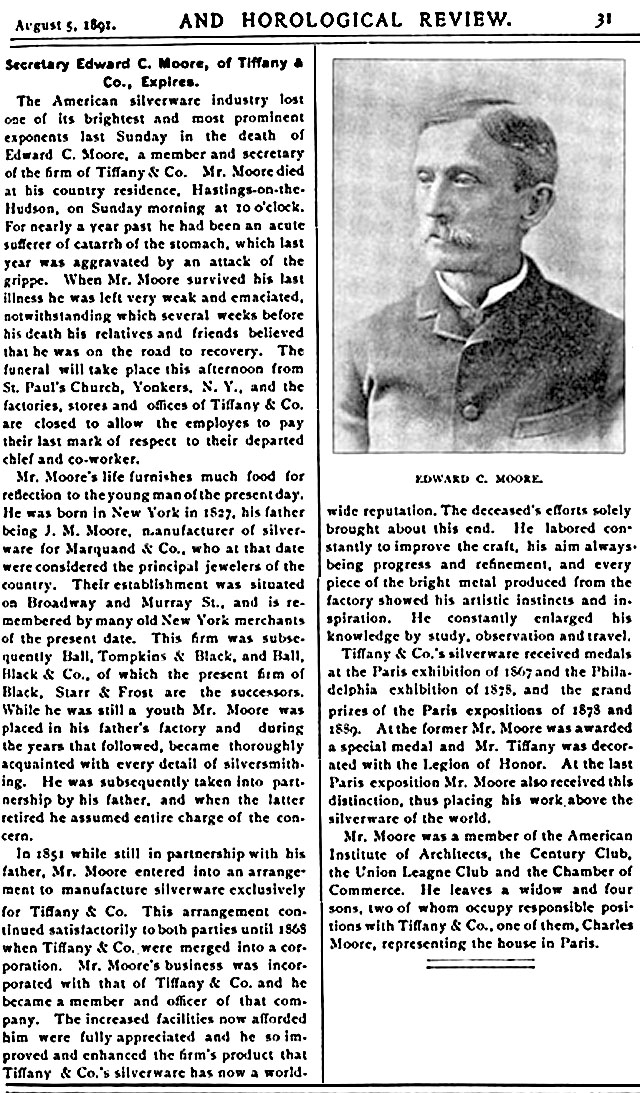

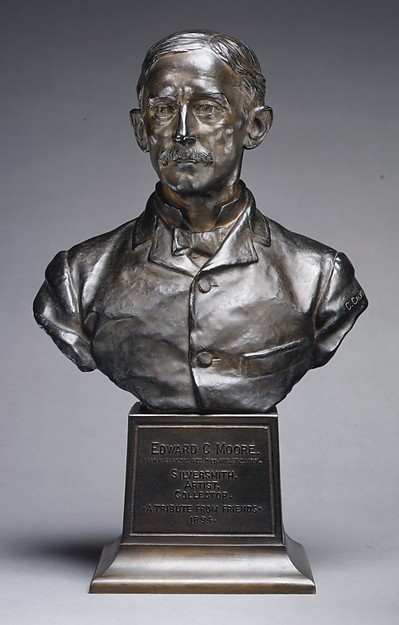

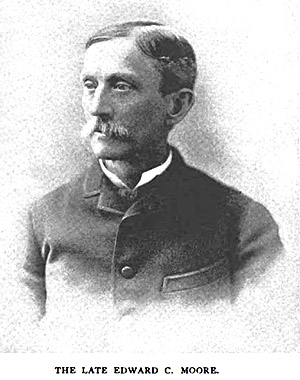

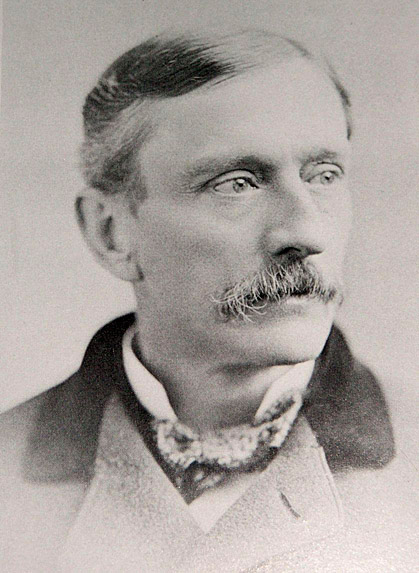

A PRINCE OF SILVERSMITHSThe late Edward C. Moore was easily the foremost silversmith in the United States. It is largely due to his skill and industry that American silverware has reached a degree of perfection that makes it celebrated all over the world. He practically developed a new industry here; but modest and retiring, almost morbidly averse to publicity of any kind, he passed through life without assuming in the eyes of the general public the credit he so well deserved. In the words of his warm friend, Mr. S. P. Avery, the world will never fully know the loss it met with In the death of Mr. Moore, and what he did for the industrial arts will never be wholly told.

He was a son of John C. Moore, who manufactured silverware for Marquand & Co., and also for their successors, Ball, Tompkins & Black. He learned h is trade in his father's shop, and was later taken into partnership, finally succeeding his father upon the latter's retirement in 185l. Before this an arrangement had been effected to manufacture solely for Tiffany & Co., which was continued until 1868 when, Tiffany & Co. becoming a corporation under the State laws, they bought the entire plant of Mr. Moore, and thereafter the establishment was a department of their general business, under the direction of Mr. Moore as an officer of the company. Early in the sixties Mr. Moore saw the need of better artistic instructions, and, realizing the meager facilities offered in this city, more particularly in the decorative and industrial arts, he set to work to establish a system of instruction and training in his Prince Street works that soon developed into the most thorough and complete school of its kind in existence. He traveled extensively abroad, and with Mr. G. F. T. Reed, the then resident partner at Paris of Tiffany & Co., made an especial study of the working of local technical schools supported by the city of Paris -- not the Ecole des Beaux Arts. This system he introduced in his own works. and with it, drawing and modelling from natural objects became a part of the education of his apprentices. Constantly seeking to improve on old methods, silversmithing and metal-working were raised by him to such a standard that they graded insensibly into the fine arts.

Mr. Moore's great forte was form and utility rather than decoration. Utility always came first, then grace and appropriateness of form. In his travels he was quick to gather ideas from the methods of metal-workers in other countries. The Persian, North of India, and Oriental schools contributed to his knowledge, but his originality was shown by the fact that his observations and constant studies and researches were ever creating and developing something peculiarly his own. A notable instance was his famous "hammered silverware," first exhibited by the Tiffany at the Paris Exposition of 1878. These wares were placed side by side with those of Elkington, Odiot, and Christophe; but by their originality of type, in method of application, and minuteness of every detail they created a perfect furor throughout Europe, and won the highest honors. Hammered silverware became the rage. The hammered surface was produced, as indicated, by hammering, the idea having evidently originated from the early method of hammering all metals into the desired form, and then removing as far as possible the marks of the hammer. Mr. Moore's unique idea was to show these blows just as made in all their severity. He embellished the general effect by oxidizing, and for decorative purposes introduced natural objects -- such as insects, birds, fishes, flowers, and foliage. These were mounted on the silver and wrought in gold of different alloys, copper, and other metals.

The amalgamation of metals, which originated with the Japanese, was another of Mr. Moore's successful studies which he perfected to a great art. This consisted of several metallic compounds worked up mechanically together, yet each of them retaining its original purity. He produced some fine specimens of this work for the Paris Exposition of 1889, noticeably a beautiful vase, standing about three feet high. His great work for this exposition, however, was Saracenic both in form and decoration. This Saracenic silverware, of which many exquisite specimens in vases, compotiers, coffee-pots, etc., are now on exhibition at Tiffany's, was the pride of his life, and to it he gave his undivided attention in preparation for the Exposition of 1889. The ware is Saracenic chiefly in the form. In the decorations Mr. Moore introduced many new features heretofore foreign to metalwork, notably the enameling of orchids, which Mr. Paulding Farnham originated in his designs for the jewellery made by this same house for the exposition, and which was also rewarded with a gold medal.

Enameling on metals was another one of Mr. Moore's favorite studies, his efforts being devoted to overcoming the glassy and glittering effects so common in Russian and Persian silverware. How well he succeeded may be seen on the beautiful work in the Saracenic ware. Orchids of many varieties are reproduced with true fidelity as to colors and every minute detail, from the stem to the tip of the leaves, in hard, dull enamels, and bear the imprint of the most marvelous delicacy and rare genius in their treatment. In some of the pieces the effect of the enameling is enriched by pierced or open work, oxidizing or stone-finish, but all of them are enhanced by the finest of etched work.

Etching on metals was another distinct branch of the industry which Mr. Moore has developed, until today it is gradually supplanting engraving.

In 1867 Mr. Moore s work received its first medal at the Paris Exposition; another medal followed it home from the Centennial in 1876; and then the honors came thick and fast. The house was appointed jewelers and silversmiths to Queen Victoria and other crowned heads. The silverware received the Grand Prix at the Paris Expositions in 1878 and 1889. When, at the 1878 exposition, Mr. Charles L. Tiffany, the head of the house, was decorated with the Legion of Honor, Mr. Moore received a special gold medal. At the exposition of 1889 he was titled Chevalier and decorated with the Legion of Honor.

Aside of his great interest and devotion to the industrial arts, Mr. Moore was a great collector of objects of art for his own home.