quote:

Originally posted by chase33:

I thought I would share this article:When I read it, I didn't know whether to be sad or angry (probably both)

On the Trail of a Silver Thief

by Kim Severson - April/May 2014

[I.] The Crime Scene

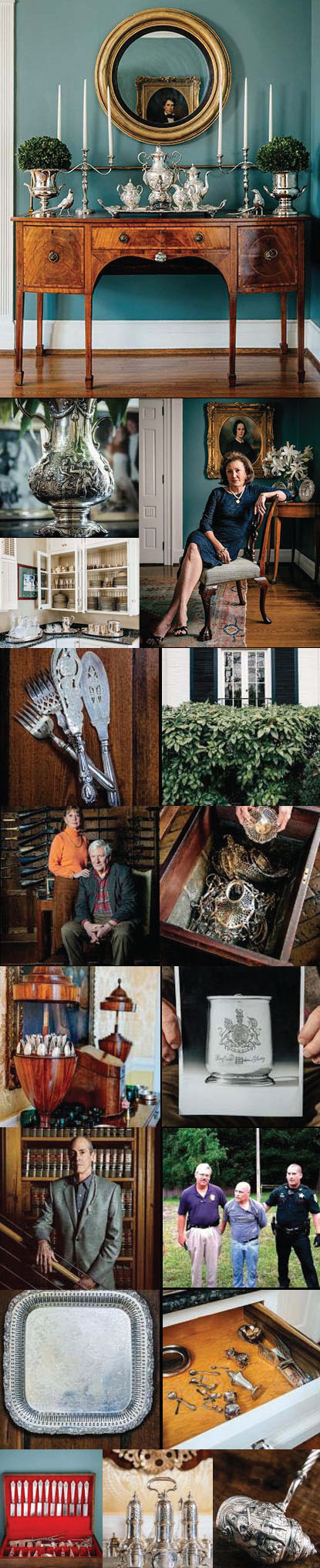

As she did most mornings, Mary Doffermyre woke up and headed straight for the thermostat in the dining room. Her husband, Everette, had a habit of turning it down. The old white brick Georgian-style house on Tuxedo Road, one of the best addresses in Atlanta, could get drafty. As she reached to turn up the heat, she noticed that her beloved art deco Tiffany tea service, the one that had been in the family for as long as anyone could remember, was missing from the sideboard.

Again, she blamed Everette. He was a noted plaintiff’s attorney, a wealthy man unafraid to take on tobacco and pharmaceutical companies. But he was always moving artwork around the house, a trait she found maddening. Then she noticed that her mother’s ornate sterling-silver compote, a foot-high beauty with little oarsmen on the top, was gone. “Everette!” she screamed as she ran back up the stairs. “We’ve been robbed!”

Sometime while the couple slept upstairs, the bedroom door locked and the dogs snoozing nearby, a thief with the precision of a craftsman had unscrewed the black wrought iron that protected the lower half of the French doors in the dining room. He eased off the putty from around the windowpanes and then meticulously stacked the thin strips of wood framing in a triangle, the way a child might assemble Legos. “They were just laid out there so neat,” Mary says. “He was so anal.”

The thief set the old window glass carefully against the side of the house and hoisted his body through the small hole. He had chosen only two rooms to rob. Crossing the hall into a living room, with pieces of silver on top of the baby grand and the bookshelves, could have set off the motion detectors. Still, the damage was devastating. He got the julep cups, three silver pitchers, and countless silver trays. Gone, too, were 150 pieces of Mary’s favorite flatware. Like so many Southern women?of a certain generation, Mary was deeply attached to the spoons and forks that marked her table at dinner parties and holiday gatherings. What was on your table said everything about you.

Looking back, she is grateful she had moved another set, her cherished Francis 1, down to the Palm Beach house. But the set she kept in Atlanta was particularly important to her. It was an antique Lansdowne pattern by Gorham, each piece monogrammed with her grandmother’s initials. She had service for twelve, both the dinner and the daintier luncheon size, along with every service piece one could imagine.

The silver thief had gotten almost all of it, right down to the butter picks and sliced tomato server. All that remained were the hollow-handled knives and the boxes, which the thief had left on the ground right where he had squeezed in through the door. The knives just didn’t weigh enough to be worth the cost of shipping them to the smelter.

On that November morning in 2012, the Doffermyres had become members of an exclusive club: victims of a silver thief investigators believe was so prolific and so skilled that for nearly three years he marched through as many as a hundred homes in the most privileged neighborhoods in six Southern states, stealing more than $12 million worth of the region’s finest sterling silver.

The theft of silver in the South is particularly painful. So much was lost during the Civil War. The pieces that remained had sometimes been saved only because someone had hidden them in a smokehouse or buried them somewhere on a plantation. Silver had also offered a way for the South to rebuild. Pulling together a new collection of silver after the war sent a signal that life would go on, and that Southern civility was not, in fact, dead.

“The silver that’s here, it fought to be here,” says John Jones, an appraiser based in Birmingham, Alabama, whose clients numbered among the victims. One family in Nashville’s Belle Meade neighborhood lost four generations’ worth of fine silver, some of which had been crafted from melted coins and hallmarked. Whether the thief knew all of this when he began raiding the richest homes in the South is still a mystery. The answer lies, at least for the moment, in the Fulton County jail in Atlanta, where the man police believe is responsible is awaiting trial.

[II.] The Suspect

Blane Nordahl, who is fifty-one, is a short, muscular, and exceedingly focused career criminal who had, until 2010, been serving time in New York for a series of silver thefts that had already made him infamous. People call him the silver thief to the stars. He has his own Wikipedia page. TV shows like Law and Order have built plots around his career.

Nordahl was a Midwestern boy with divorced parents who dropped out of high school in the eleventh grade and joined the navy, only to be discharged after he deserted. His first burglary arrest came in 1983, when he was a two-bit criminal just learning the craft. By the 1990s, he was devouring architectural magazines and learning all he could?about silver. And he was becoming a better thief, learning how to enter homes without leaving a trace save a small passage where he fastidiously removed a window or the panel of a door. He became a master at slipping past dogs and alarm systems, often doing such a clean job that people had no idea they had been robbed until it came time to pull out the silver for a holiday.

He went for colonial silver in Philadelphia, Boston, and Baltimore and took coin silver pieces from high-end homes in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, and Winnetka, Illinois, a community of expansive mansions on Lake Michigan. He slipped away with a quarter million dollars’ worth from a home in Essex Fells, New Jersey. Investigators say he even stretched his enterprise to Palm Beach back then, once hitting the home of the sportscaster Curt Gowdy.

In 1996, he took more than $150,000 in silver from Ivana Trump’s house in Greenwich, Connecticut, and a load of Francis 1 cutlery, a pattern ripe for the taking in Southern homes, from another Greenwich residence. He was caught and charged for those and a handful of other burglaries in upstate New York, and served a relatively short sentence after he admitted his role in 144 burglaries in several states. He was released after just a few years and got right back to stealing silver.

In 2002, he worked New York’s Hudson Valley. The most stunning jobs involved the priceless collection of period silver contained in the Edgewater mansion, assembled with great research and several trips to Europe by Richard Jenrette, a Southern-born Wall Street financier and restorer of historic homes, and a collection from the Wilderstein estate, the former home of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s cousin.

By 2004, he was sentenced to eight more years in prison. He got out six years later and immediately headed to Jacksonville, Florida, where his sister lived. Like Sherman, the nation’s most notorious silver thief, investigators say, was planning to march through the South.

[III.] The Sting

Lonnie Mason, a retired New Jersey detective, is a balding, straight-talking father of four children, three of whom are turning out to be cops, too. He’s a fan of the New York Giants and the Mets who lives a couple of blocks from the Jersey shoreline. He started his police career the day he graduated from high school, and he is the person in the country most singularly obsessed with Nordahl.

“Blane and I hate each other,” he says. “We love to hate each other.”

Mason started investigating Nordahl in the 1980s, trying to solve some petty burglaries in the shore town he patrolled. Nordahl wasn’t involved, but Mason soon connected him to other crimes. He’s talked to Nordahl on more than two dozen occasions and arrested him five or six times, in conjunction with other jurisdictions.

Once, he nabbed him in a motel room. Nordahl was hiding behind the door. The two ended up wrestling on the floor, and Mason found himself staring at a tennis shoe whose tread would be matched to a footprint on a counter at a crime scene—a rare mistake Nordahl never made again. After that, he took to wearing layers of socks and shoes a couple of sizes too big.

Mason is an old-school gumshoe who has embraced the digital age. Once he heard Nordahl had made parole, he felt certain the thief would be at it again. “He is what he is,” Mason says. “He is a real whack job when it comes to silver. This is his high—this and trying to beat the police.” One ex-girlfriend told Mason that Nordahl would be eighty years old and still running down the street with his cane and a piece of silver in his hand. “He is just fascinated with this stuff,” he says.

When he learned Nordahl had headed for Florida, Mason sat down at his computer. For months, he plugged the words silver and thefts and burglaries, along with Florida, into the search engine. In March 2013,?he started adding other states. He got a hit in Georgia, a report on burglaries in Buckhead. All the hallmarks were there. Remarkable pieces of silver lifted from rich neighborhoods in the middle of the night, with nary an indication the homes had been robbed.

He got on the phone, cold-calling detectives to say he knew who was doing the crimes. One can imagine the reaction. “Southerners aren’t very accepting of Northern ways,” Mason says, “and here I am this damn Yankee telling the Southerners I know who is doing this.” Eventually, he convinced Drew Behry, a detective in Atlanta, to listen.

“I’m going to tell you how the glass was cut out,” Mason told him. “I am going to tell you the corner he started with. It will be pressed in harder than the others. Then he goes clockwise.” Mason had so many details right, the officer was stunned. “Either you did the job or you were with the guy who did the job,” Behry told him.

Investigators arrested Nordahl last August, using a mix of technology and old-fashioned police work. For months, law enforcement officers had tracked his movements with cell-phone records and public cameras. They figured out which motel rooms he was staying in, knowing he didn’t spend more than a hundred dollars a night, and tracked the nice rental SUVs they say he preferred so he would better fit in with the neighborhoods he was prowling. They went over his bank accounts, used phone records to find the New York and Pennsylvania smelters where he allegedly shipped the silver to be melted down, and discovered the UPS store he used, intercepting a few boxes in the process.

Then they got to his new girlfriend, a Florida woman named Elizabeth Irene Music, with whom he began a pool service company that may or may not have been a front to funnel silver money. Investigators who have plowed through Nordahl’s phone records for years say he was a great lover of pornography and sometimes visited prostitutes. But he had had a string of girlfriends over the years, vulnerable women he would attract and spend money on, coercing them into becoming accomplices. Music was a perfect target for Nordahl. She had no record, but she was lonely and had financial trouble.

“She was like finding a lost puppy,” Mason says. She was afraid of Nordahl and afraid of jail, and she wanted to protect her daughter, who sometimes, according to officials, received the checks Nordahl would have shipped from smelters. So she cooperated, even driving around with detectives in the Atlanta neighborhoods where she said Nordahl had worked his craft.

When the police arrested her on August 24, she told them they could find him at home in Jacksonville. Dozens of officers arrived to arrest him. The house was virtually surrounded, but Nordahl, inexplicably, managed to drive his car past an officer, waving as he went. “It was,” says Mason, “a screwup.”

Nordahl headed to Georgia, but investigators say he knew he had cash coming in from his latest shipment. Two days later, he called Music’s daughter and arranged to pick up some checks from her place in Hilliard, Florida. The cops were waiting. But as he was pulling into the apartment complex, Nordahl made out a surveillance team. He jumped out of the car and, as he had done plenty of times before, he ran. Officers began the chase through the grass surrounding the apartments. They were losing ground when a man in his sixties saw a short figure scrambling through the complex. He figured it was a teenager who had done something wrong. He tackled him.

As Nordahl was sitting on the grass, hands cuffed behind his back, the arresting officers called Mason. His nemesis, they told Nordahl, was on the phone. The suspect just lowered his head to his knees. “If it wasn’t so early in the morning,” Mason says, “I would have had a cocktail.”

Nordahl is currently waiting to be tried on eight burglary charges, one of which is Mary Doffermyre’s. Music is facing the same counts and will be tried in Fulton County along with Nordahl. As of earlier this year, she was out on bail in Florida. A bad back from a recent car accident and a case of pneumonia have kept her from appearing at any of the hearings that have been scheduled as the case works its way through a backlogged system. It will be months before they go to trial.

After the cases in Atlanta are completed, Nordahl will face similar charges in Brunswick, Georgia, and finally in Aiken, South Carolina. Those jurisdictions have the strongest cases. In South Carolina, burglars?who have been convicted on similar crimes in the past and committed the new crime when someone was home at night face life in prison.

There is no way, Mason says, he will ever get out again. At least if things go the way he and other investigators believe they will.

[IV.] The Lawyer

Previous defense attorneys say Bruce Harvey, Nordahl’s current counsel, has his work cut out for him. Nordahl, who lays out his own detailed legal strategies in tiny, neat print, is an extremely controlling client who will work every angle and thinks he knows better than any lawyer how to beat his case.

Harvey isn’t worried. He says he has plenty of legal leverage, and that Nordahl will continue to fight to prove his innocence. But still, Harvey says, his client realizes he is in a tight spot. “He’s been down this road a number of times and now people are not going to be as forgiving as they were in the past.”

Like most who come into Nordahl’s orbit, Harvey is intrigued. But he is not enamored. He says Nordahl, who would not agree to an interview for this story, doesn’t come across as a brilliant, physically fit mastermind able to elude manhunts and haul a hundred pounds of silver out of a house in a duffel bag. He looks, Harvey says, like one of Santa’s aging, pudgy elves. Still, he has the steely confidence of a man who enjoys being Blane Nordahl, silver thief to the stars. “You get to a point in your life,” Harvey says, “where you want to live up to your own reputation.”

[V.] The Victims

For a few of the people involved, there is some small comfort in believing they were bested by the world’s greatest silver thief. It certainly made the theft at the Buckhead home of Beverly “Bo” DuBose III, a real estate developer and noted collector of Civil War artifacts and exquisite Chinese porcelain, something more than your average home burglary.

While Bo and his wife, Eileen, slept during a stormy June night in 2013, the silver thief removed a couple of panes of glass by carefully prying the putty from the windows with a small knife. The security cameras in the house were outdated. Whether the thief knew that remains a mystery, but it seemed as if he did. No images were usable. As Nordahl did in most of his work, the burglar who hit the DuBose house left the felt bags that had cradled the silver folded neatly in the drawers. And as Nordahl had done in past burglaries, the thief took entire trays of silver outside. He kept the heaviest flatware, leaving the hollow-handled knives in their case near the spot where he made his entrance and exit.

The couple left the next day for a trip, unaware they had been hit. When they discovered the theft, the loss was devastating: $177,000 worth of silver, including a rare cake basket made in the eighteenth century that the DuBose family kept in the dining room, a fifty-two-piece silver flatware set, and, perhaps most painful of all, a small pint mug from 1734 that was connected to King George II. Nonetheless, Bo is a bit philosophical about it all. “To be here asleep and have it happen, you realize how good he really is,” he says. “He was the best of the best.”

Other victims have been more traumatized. A woman in Aiken, South Carolina, one of six cases there, had just brought her husband home from hospice care when a man police suspect was Nordahl slipped in.

In Columbus, Georgia, a woman woke her husband up when the alarm to the silver closet went off. He went downstairs and closed the door, figuring the old lock was just acting up again. Police believe Nordahl was in the house, hiding until the man went back to bed. The next morning the couple saw wood missing from the door but assumed the men who had been working on the house had perhaps started early. But then they noticed a cloth napkin on the ground outside. They won’t talk about it publicly for fear something they say might ruin the legal case against Nordahl. And they won’t reveal what was taken. One thing that was spared: a pair of sterling candlesticks the woman had put in the freezer, using an old trick to help remove candle wax.

John Jones, the appraiser, says his clients in Nashville—some of them quite elderly—are still shaken. Seven homes in Belle Meade were hit over an eighteen-month stretch from 2011 to 2013, among them the estate belonging to the widow of Jack Carroll Massey, who once owned Kentucky Fried Chicken and one of the nation’s largest Wendy’s franchises.

The thief also tried and failed at two other homes, one of them a mansion that appears regularly in the television show Nashville. In the aftermath, many people with extensive silver collections in the city are considering selling them. Better they end up in the hands of someone who loves them than a silver thief’s.

The losses were historically devastating, too. In October 2011, the thief hit the Cooleemee Plantation House in North Carolina, a historic landmark that has been in the Hairston family since 1817. According to Davie County detective Scot Kimel, the thief was particularly careful about how he made his entry. He disabled the alarm system wire by wire, waiting an hour after each cut to see if there was a police response or a signal from the alarm company. Then he cut the phone lines. He made his entry through a window, and spent an hour and fifteen minutes inside the house, never once crossing a motion detector. He walked away with an antebellum tea set that historians say a slave named John Goolsby had hidden in the woods until Union troops had passed by. He also got a dozen silver spoons forged by Paul Revere, a prize so rare Mason suspects Nordahl might have kept them for himself.

For most victims, the lost silver was an irreplaceable link to their history and their ancestors. They had become caretakers of the family legacy, and in a flash, it was gone.

Kathleen Hohlstein had left her silver locked inside the silver closet in her Green Island Hills home in Columbus, Georgia, when she and her family were transitioning to Atlanta. They had set the alarm, put the lights on timers, and parked a car in the driveway. Still, the thief got in. Had he watched the neighborhood? Had he used Google to find their address? Did he find the neighborhood or even specific victims in publications that highlighted the glorious homes of the South?

All of it, detectives say, is possible. Nordahl was a researcher who knew how to find the homes that would yield what he was after. He once bragged that he had no scent dogs could detect, and he understood the habits of people lulled into complacency by the promise of expensive alarm systems and the limitations of small-town police departments. It would be nothing, detectives say, for Nordahl to hike a mile or more from his car to avoid detection, or hide out in a nearby field until a thunderstorm reached its noisy peak to mask his break-ins.

No one knows if it was Nordahl who entered Kathleen Hohlstein’s house, but she is sure he’s the one who stole her most emotionally priceless belongings. Gone is her great-grandmother’s flatware, the Gorham Buttercup pattern with serving spoons bearing a 1909 monogram. “It was just precious to me as an heirloom,” Hohlstein says. Gone, too, is a silver service from her grandmother, who had married during the Depression. The burglar took a tea urn connected to General Henry Martyn Robert, who wrote Robert’s Rules of Order, twelve hammered silver goblets, and an 1847 presentation ewer made by Bailey and Kitchen. And in a particularly painful move, the thief took the julep cups her mother had been giving her sons, one each year, until they each had a set of six.

Hohlstein and the other victims pore over every detail of the case against Nordahl, showing up on the days he is scheduled for court hearings and sharing information as they try to piece together what happened to them. “I would like to lay an evil eye on him and just hope he doesn’t slip away,” she says. “I hope that the Atlanta judge and the other judges that do actually sentence him will not be light.”

They also realize they may not be the most sympathetic victims. People have suffered more violent crimes. There is a tendency, they understand, for people to dismiss their loss as material, as a small financial blow to a class of people who have plenty and are most likely well insured. And most of them, correctly it seems, have given up hope that they will ever see their silver again.

As part of the investigation, police found a storage unit Nordahl rented. There was a welcome mat on the floor and a weight system. He would place the South’s priceless silver on the rug, police say, and smash it flat with a small dumbbell. Then he would pack it into small boxes and ship it to smelters up north, getting in return checks that averaged around $3,700.

Police intercepted a few boxes, but most of the silver is gone. What the victims hold out for now is justice, something Mason believes will come. After more than thirty years, and countless family events missed, numbing stakeouts, and legal documents, after what seems like a lifetime of days that started before dawn and ended well after midnight all in pursuit of one criminal, Mason says this is where the story will end. The man he has built a career studying, whose body language and disposition and methodology he knows by heart, will not get away this time. The country’s most notorious silver thief has made his last stand in the South. “He has finally come to the end of the line,” Mason says. “He doesn’t know how well he is had.”

SMP Silver Salon Forums

SMP Silver Salon Forums

Silver Stories

Silver Stories

The Silver Thief - Blane Nordahl

The Silver Thief - Blane Nordahl